Graphite, although it may be pure, can have poorly defined physical properties due to a close association with other forms of carbon, such as char, lampblack and soot. Perfectly crystalline graphite has a brilliant silvery surface and planar morphology but it is dark grey in the polycrystalline form. An ungraphitized carbon does not mark paper, whereas graphite will.

Graphite consists of layers of hexagonally arranged carbon atoms in a planar condensed ring system with each carbon 0.142 nm from its three nearest neighbors. The layers, termed grapheme layers, are stacked parallel to each other in a three-dimensional structure. The chemical bonds within the layers, between each carbon atom, are covalent with sp2 hybridization; each hexagonal array forming six σ bonds and the remaining ρ orbitals, which are at right angles to the layer planes, take no part in theσ hybridization. Theρ orbitals of two neighboring carbon atoms overlap sideways and formπ orbitals, with three above and three below the σ orbital plane. The π orbitals in each hexagonal array overlap and encircle all six carbon atoms taking up the form of a doughnut and the six electrons become delocalized throughout the π orbital, which lowers the energy and helps to stabilize the molecule. The planes are 0.335 nm aprt, denoting that they are held only with weak forces, which are comparable with van der Waals forces. Is should be noted that at the edges of the grapheme planes there will be loose carbon atoms, or dangling bonds, resembling cut chicken-wire netting.

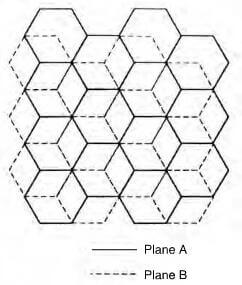

schematic of hexagonal graphite crystal

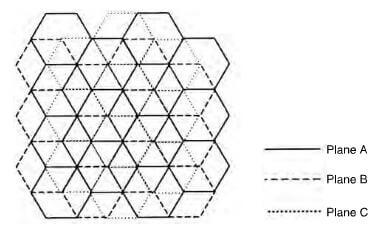

schematic of rhombohedral graphite crystal

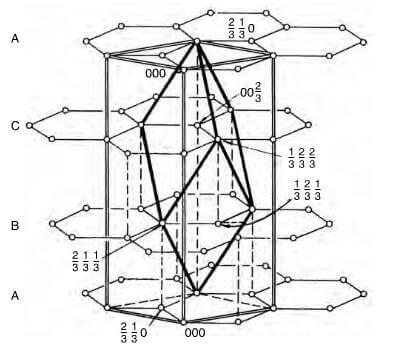

The stacking of the layer planes occurs in two quite similar crystal forms-hexagonal and rhombohedral. Hexagonal is the most common form with ABABAB packing sequence and the four atoms of the unit cell are at positions: (0,0,0), (0,0,1/2), (2/3,1/3,0) and (1/3, 2/3, 1/2). The rhombohedral form with an ABCABC packing sequence and the six atoms of the unit cell are at position (0, 0, 0), (2/3, 1/3, 0), (0, 0, 2/3), (2/3, 1/3, 1/3), (1/3, 2/3, 1/3) and (1/3, 2/3, 2/3). Thombohedral graphite is always found in association with the hexagonal form and on heating to about 2500C, the rhombohedral packing is transformed to the hexagonal form. A network of substantially perfect hexagons with parallel layer planes, but with no ordered stacking sequence, is termed turbostratic.

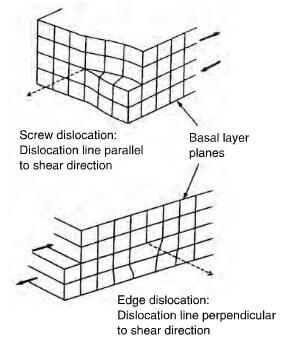

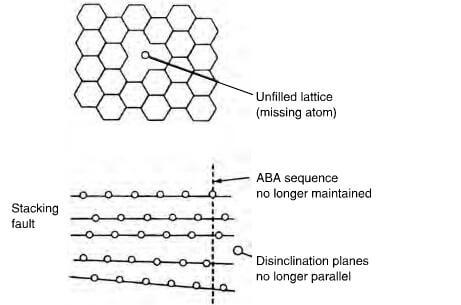

Ideal graphite does not exist and the ideal crystal forms invariably contain defects, such as vacancies due to a missing atom, stacking faults and disclination as depicted in figure 2.18. Other defects include screw and edge dislocations. Edge defects find some way of satisfying the electronic valencies and, for example, foreign atoms such as –H, -OH, -O and –O- can be bonded onto these edge defects. However, the network does buckle and bulge to accommodate such groups. Grinding graphite into a powder breaks up some of the bonds and increases the number of defects. Incorporating boron into the structure yields carbons with lowered electrical resistivity and a positive temperature coefficient of conductance. Presumably, boron provides electron acceptor sites. For valency reasons, some of the joins in the net are broken and this could explain why boron aids the graphitization of carbon.

shear disiocations in a graphite crystal

Rhombohedral unit cell structure of graphite

Schematic of crystallite imperfections in graphite showing unfilled lattice, stacking fault and disinclination.